Manual codes for English (MCEs)

Understanding transliteration morphology

Transliterating between spoken English and codes of English is not the same as interpreting between spoken English and American Sign Language. Transliterators need to have familiarity with and skill in a variety of representations of both spoken English and English-bound sign systems to produce their work.

Here are some bullet points/learning outcomes of which we might want to be aware:

- What roots and overlaps do signed languages, American Sign Language, and other spoken languages share?

- Where did manual codes of English (MCEs) like Signed English and SEE originate and how are they produced?

- What is the difference between a manual code for English and an approach for representing spoken English?

- How is jargon (situational language) manifest in interpreting events? How do interpreters learn these signs?

Readings/Discussions

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

Handout (Stringham) Required

A comparative language continuum demonstrating the overlapping relationship of American Sign Language and English which result in contact sign and manually coded English (MCE) forms and approaches (PSE, CASE, SSS, SimCom, TC, etc.). Identifies and briefly describes the most commonly known and/or used languages and MCE forms and approaches.

Code choices and consequences: Implications for educational interpreting (Davis)

(pp. 123–131) Discusses implications and impacts of MCE use on educational participants and consumers

Davis, J. (2005). Code choices and consequences: Implications for educational interpreting. In M. Marschark, R. Peterson, and E. Winston (eds.) Sign language: Interpreting and Interpreter Education — Directions for Research and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Readings/Discussions

General Principles: Manual Codes for English (MCEs)

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

Manual Codes of English Required

Manual Communication Methods

American Sign Language: A teacher’s resource text on grammar and culture (Baker-Shenk & Cokely) Required

(pp. 65–71) One of the original descriptions (1980) of English-bound sign systems, the ‘Green Book’ was the source for this information for at least 10–15 years.

Baker-Shenk & Cokely, D. (1980). American Sign Language: A teacher’s resource text on grammar and culture. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

Contrived sign languages (Crystal & Craig) Recommended

(pp. 161–66) Significant discussion about what constitutes languages (pp. 145–148) and what constitutes a signed language (156–161). Basic abstracts for ‘contrived’ sign languages (SEE1 and SEE2, Signed English, etc.) are given.

Crystal, D. & Craig, E. (1978). Contrived sign language. In I. M. Schlesinger & L. Namir, Sign Language of the Deaf: Psychological, Linguistic, and Sociological Perspectives. New York: Academic Press.

So, why do I call this English? (Sofinski)

(pp. 28, 30–32) Description of the ASL/English-bound sign system continuum, including contact sign and Pidgin Signed English (PSE) and how they are manifested in signers.

Sofinski, B.A. (2002). So, why do I call this English? In C. Lucas (ed). Turn-taking, fingerspelling, and contact in signed languages, 27–50. Washington, D.C., Gallaudet University Press.

Rethinking total communication: Looking back, moving forward (Mayer)

(pp. 5–7) Brief description of CASE and its place in the overal spectrum of English-bound sign systems and approaches.

Mayer, C. (2015). Rethinking total communication: Looking back, moving forward. In M. Marschark & P. E. Spence, (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies in Language. Oxford University Press: New York.

Contact sign, transliteration and interpretation in Canada (Malcolm)

(pp. 110–111) A brief description of English-bound sign systems within the framework of ‘contact sign.’

Malcolm, K. (2005). Contact sign, transliteration and interpretation in Canada. In T. Janzen, (ed.). Topics in Sign Language Interpreting. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Signed English

Readings/Discussions

Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE) and Sign Supported Speech (SSS)

Most popular English-bound contact sign approaches in the United States:

- CASE (Conceptually Accurate Signed English) is a popular alternative to Signed English, sometimes called PSE (Pidgin Signed English); combines ASL signs and concepts in an MCE form. Not a language.

- SSS (Sign Supported Speech) consists of voicing spoken English and signing an MCE. Sometimes called Simultaneous Communication (SimCom) or Total Communication (TC). Not a language.

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

Rethinking total communication: Looking back, moving forward (Mayer) Required

(pp. 5–7) Brief description of CASE and its place in the overal spectrum of English-bound sign systems and approaches.

Mayer, C. (2015). Rethinking total communication: Looking back, moving forward. In M. Marschark & P. E. Spence, (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies in Language. Oxford University Press: New York.

Adverbials, constructed dialogue, and use of space, oh my!: Nonmanual elements used in sign language (Sofinski)

(pp. 176–177) Brief description of CASE and an argument against its classification as a language or preferred interpreting approach.

Sofinski, B. A. (2003). Adverbials, constructed dialogue, and use of space, oh my!: Nonmanual elements used in sign language. In M. Metzger, et al. (eds): From topic boundaries to omission; New research on interpretation, 154–186. Studies in Interpretation Series. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Some characteristics of Pidgin Sign English (Woodward)

(pp. 40–41) Seminal description and discussion of Pidgin Sign English as a means to address diglossia in the Deaf/ASL-using community.

Woodward, J. C. (1973). Some characteristics of Pidgin Sign English. Sign Language Studies, 3(1), 39-46.

“What do you guys think about CASE?”

Now-finished forum discussion at alldeaf.com containing a mixture of academic resources and deaf consumer perception of how/when interpreters use a CASE approach in their work.

When is a pidgin not a pidgin? (Cokely)

Cokley disagrees with Woodward and other contact sign researchers and provides an alternative view at the ASL-English contact event, arguing that the requirements for a pidgin language are not met.

Cokely, D. (1983). When is a pidgin not a pidgin? An alternate analysis of the ASL-English contact situation. Sign Language Studies, 38(1), 1-24. doi: 10.1353/sls.1983.0017

Readings/Discussions

Signed English

Now largely defunct. Simplified English-based code; only 14 added grammatical markers. (Developed mid-1970s, Harry Bornstein, Gallaudet College; 1983, Bornstein, Saulnier, & Hamilton)

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

The Comprehensive Signed English Dictionary (Bornstein, et al) Required

(pp. 3–8, 10–24) The preface to The Comprehensive Signed English Dictionary by Bornstein (1983) explains some of the methodology behind Bornstein and Saulnier’s MCE system. Describes SE’s affixes and rationale behind their sign creation rules. (Check out the first line of page 3!)

Bornstein, H., Saulnier, K, & Hamilton, L. (1983). The comprehensive signed English dictionary. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

Signed English: A Manual Approach to English Language Development (Bornstein)

(login required) Bornstein, H. (1974). Signed English: A Manual Approach to English Language Development. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders (August 1974), Vol. 39, 330-343. doi:10.1044/jshd.3903.330

Readings/Discussions

Seeing Essential English (SEE1)

Now defunct. Intended to reinforce basic English morphemic structure (compound words are formed with separate signs; one sign used for homonyms; heavy use of initialization (haVe); added affixes, articles, and ‘to be’ verb) (Developed 1966, David Anthony, Gallaudet College)

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

A History of Seeing Essential English (SEE1) (Luetke-Stahlman & Milburn)

(pp. 1–3) Historical development and research into the use of SEE1.

Luetke-Stahlman, B., & Milburn, W. O. (1996). A History of Seeing Essential English (SEE1). American Annals of the Deaf, 141(1), 29-33.

Seeing Essential English: A sign system of English (Washburn & Anthony) Required

(pp. 18–22) Gives a history of and an explanation of some of the production rules for Seeing Essential English (SEE1) by the inventor.

Washburn, A. O., & Anthony, D. A. (1974). Seeing Essential English: A sign system of English. Journal of Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology, 7(1), 18-25.

Readings/Discussions

Signing Exact English (SEE2)

Most commonly-used manual code system in the United States. Similar to SEE1 but strives to be semantically closer to ASL (compound words conceptually accurate; homonyms produced semantically; several artificial/invented signs and affixes) (Developed 1972, Gerilee Gustason)

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

Signing Exact English (Gustason) Required

(pp. 108–127) This article by Gustason (in Bornstein, 1990) examines the origins of the SEE and LOVE MCEs. Particularly helpful in clarifying LOVE and reasons for and myths about SEE creation and usage.

Gustason, G. (1990). Signing Exact English. In H. Bornstein (ed.) Manual Communication: Implications for Education. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

“SEE: Allow me to disabuse you of a common misnomer” (Greene) Required

Interpreting colleague Daniel Greene attempts to dispel misinformation and clarify the use of SEE2 for other interpreter practitioners. “My desire is for people to make educated choices about the language they use, which is why I want to make sure people who use the term SEE know what it actually is.” Includes video of SEE2 users.

Comparing an ASL and SEE2 rendering

Watch a (simultaneous) text rendering in ASL and SEE2. Rhetorical and political feelings aside, what is happening in the SEE2 text?

Star Spangled Banner Parody - Mr. SeeTerp

The Mr. SeeTerp parody character created by artist John Maucere demonstrates how ‘survivor’ humor is derived out of an over-the-top use of SEE as a communicative platform. SEE is often used in Deaf discourse as a marker; those who use it are not ‘us,’ but ‘them.’

Readings/Discussions

Linguistics of Visual English (LOVE)

Now defunct. Little to no extant documentation on the LOVE system. Based on Seeing Essential English (SEE1). Used Stokoe Notation System (tab-dez-sig; Stokoe, 1960; Stokoe, Casterline, & Croneberg, 1965) to codify. Defunct. (Developed 1972, Dennis Wampler)

Kelly, Transliterating: Show Me The English

Chapter 1 (pp. 4–6) Required

The Deaf Community in America: History in the Making (Nomeland & Nomeland)

(p. 122) Brief description of Wampler’s LOVE system, highlighting its 1:1 coding and heavy use of initialization. (Other excellent brief descriptions of other English-bound sign systems also listed here.)

Nomeland, M. M. & Nomeland, R. E. (2011). The Deaf Community in America: History in the Making. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Signing Exact English (Gustason)

(p. 112) This article by Gustason (in Bornstein, 1990) provides a brief description of the origin and use of Wampler’s LOVE system.

Bornstein, H. (ed.) (1990). Manual Communication: Implications for Education. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

The history of language use in the education of the Deaf in the United States (Lou)

(p. 92) Comprehensive article on the evolution of language usage in American deaf education. Brief(!) description of LOVE and how it was implemented in schools. (Lots of other bonus information about other English-bound sign systems and approaches also given here.)

Lou, M. W. (1988). The history of language use in the education of the Deaf in the United States. In M. Strong (ed.) Language Learning and Deafness. London: Cambridge University Press.

Readings/Discussions

Rochester Method/other manual alphabet methods

Now largely defunct. Each lexical unit solely produced using the manual alphabet. Extensively used in schools for the deaf in the late nineteenth century. Sometimes used in tactile/deaf-blind signing situations. (Developed 1878, Zenas Westervelt, Western New York Institute for Deaf-Mutes, later Rochester School for the Deaf)

Methods of Instruction in American Schools for the Deaf

This article, and the subsequent article by Zenas Westervelt, gives historical context to the rise of a manual English teaching and communicative method in the 1870s and 1880s.

How the Alphabet Came to Be Used in a Sign Language (Padden & Gunsauls) Recommended

(p. 13) Historical context for Westervelt’s proposed perspective (“The Disuse of Signs”) of the relationship between signs and the manual alphabet and how fingerspelling/the alphabet is used by signers today.

Padden, C. & Gunsauls, D. (2003). How the alphabet came to be used in a sign language. Sign Language Studies, 4(1), 10-33.

The Rochester Method (Castle)

(pp. 12–16) Early description and discussion of simultaneous spoken English and manual alphabet (fingerspelling) as a teaching option in the United States and in other countries.

Castle, D. (1974). The Rochester Method. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology, 7(1), 12-18.

The importance of fingerspelling for reading (Baker) Required

(pp. 4, 6 impact interpreter/transliterator usage) Early description and discussion of simultaneous spoken English and manual alphabet (fingerspelling) as a teaching option in the United States and in other countries.

Baker, S. (2010). Research brief No. 1: The importance of fingerspelling for reading. NSF Science of learning Center on Visual Language and Visual Learning, Gallaudet University.

Some argue that fingerspelling doesn’t belong in ASL, but what about English bound signing? What is its role in interpretation? In transliteration?

Readings/Discussions

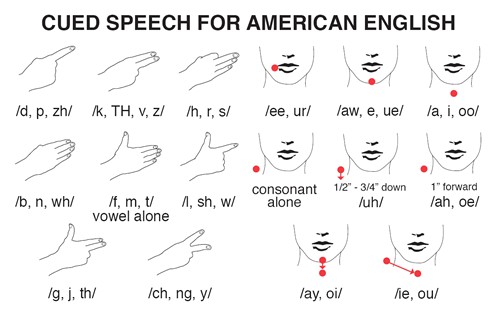

Cued Speech

A visual phonemic manual code for English; not a signed language. Combines eight arbitrary handshapes and four locations to visually and phonetically represent English. (Developed 1966, Dr. Robert Orin Cornett, Gallaudet College) What are the benefits in knowing this? How does it help Deaf students?

Cued Speech sample

Cued Speech Association YouTube channel

Learning to Cue: Lesson 1 and Lesson 2 with a Deaf cued user

Readings/Discussions

Paget-Gorman Signed Speech

British-based pantomimic, morphological based manual system. Developed 1934, Sir Robert Paget)

Development of the Paget-Gorman Sign System

Although the first experimental teaching of the system began in 1964 with a group of deaf adults, PGSS was first conceptualized in the United Kingdom in 1934 as a systematic pantomimic sign language whereby each word would have its own sign, with the signs presented in the same sequence as the words in the phrases or sentences to be signed.

Basic Signs in the Paget-Gorman System

Paget Gorman Sign Speech also has a YouTube channel.