Comparative ASL and English Language ContinuumBeta

For use with Transliterating and Interpreting Studies classes.

See this continuum also on Notion.

Version and currency

This HTML/hypertext version () supercedes any of the popular printed versions in that 1) it is more easily updated/distributed and 2) allows for additional footnoted and documented hypertexted media (research/text, video, etc.). This version also supercedes any other existing printed versions as well as the version printed in HumphreyHI, J., ClarkHI, L., FeatherstoneDI, J., and Ross IIIHI, W. F. (2020). You want to be an interpreter (5th edition). Vancouver, WA: H&H Publishing.

All implied placements and relationships are relative; overlapping approaches drawn for distinction and not for accuracy. Subscripts on surnames (e.g., D, DI, H, HI or ?) identify that an author, researcher, contributor, or creator is Deaf, hearing, also an interpreter, or unknown. Additional credit to authors DParvazHI, Garrrett?, Jguk?, Adrignola?, and other unnamed contributors to the Visual Language Interpreting/Tools of the Trade wikibook for references to dates, contributors, and descriptions.

For clarity in modality, this document makes a distinction between SLs (sign(ed) languages) and SpLs (spoken languages), while also recognizing that linguistically and academically, a signed language can be 'spoken.'Purposes & Definitions

Diglossia

This is a comparative bilingual continuum for use with Deaf and Interpreting Studies students that identifies the diglossic and representative relationships of artificial (or 'contrived') manual codes of English (MCEs) historically derived between American Sign Language (ASL) and English.

The principle of contact sign systems is operational for other signed language code variations and adjacent spoken languages.

Identify

It identifies 1) creators and contributors, 2) cultural (Deaf, hearing, or interpreter) status, and 3) MCE 'approaches' and other gestural MCEs that are English-derived but that may also be used with various deaf populations. (This code and content should be considered 'in development'; see this project's changelog and roadmap below.)

Document

There are numerous sites and articles (and student projects) across the internet that mention or discuss this unique set of systems, their etymologies, variables, and pedagogical aims. This compilation is intended to empirically document this domain for students, colleagues, and other researchers. Feedback, additions, and corrections are appreciated.

Educate

Rhetorically, this artifact, while intended for a greater contribution to histories and historiographies in our field, is for discussion by Deaf and Interpreter Studies students in learning more about the praxis — but certainly not the advocacy for use — of these codes in educational and interpreted work. A future section of this artifact should/will likely be 'learning objectives.'

"Code"

(In development.) 'Codes' differ from 'approaches' in that they are relatively defined (albeit loose or dotted-line) established manual representations of spoken English that follows fairly accepted lexical items and linguistic rules. (Add more here; Riley (2011), Crystal & Craig (1978) to define 'code')

"Approach"

(In development.) Approaches differ (and are visually designed differently) in that there are nuances in how principles of CASE or SSS are 'used' to render a transliteration.

Continuum

⇠ American Sign Language

(principle is operational for other SLs)

English ⇢

(principle is operational for other SpLs)

⇠ MCE approach

A Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE)

Popular alternative to Signed English, previously called PSE (Pidgin Signed English). Combines ASL signs and semantics in an MCE form. Not a language.

MCE approach ⇢

B Sign Supported Speech (SSS)

Voicing spoken English and signing an MCE. Sometimes called Simultaneous Communication (SimCom) or Total Communication (TC). Not a language.

1

4

2

3

5

6

8

7

Manual Codes for English

1

American Sign Language (ASL)

Visio-gestural, preferred, and connate language of Deaf people of the United States and Canada. Also historically exported to/creolized with other national Deaf educational efforts in African and Asian countries. Etymology and roots in:

- Indigenous, regional, un- or marginally-recorded, and unknown SLVs

- Native American SLVs (ClarkHI, 1885; DavisDI, 2017)

- Black SLVs (HillD, McCaskillD, BayleyH, & LucasH, 2015; McCaskillD, LucasH, BayleyH, & HillD, 2020)

- British/Kentish/Vineyard SLVs (GroceH, 1985; c.f., KitzelH, 2013)

- Mexican SLVs (Quinto-PozosHI, 2002; 2008)

- French SLVs (PelissierD, 1856; LaneH, 1984; )

- Cistercian monk SLVs (CagleDI, 2010)

First documented in BrownH, 1856 and 1860 (StringhamHI, 2019). Topic-comment grammatical structure and approach (cf. Baker-ShenkHI & CokelyHI, 1980); utilizes code-borrowing from majority spoken language. Also called ‘the sign language’ (VeditzD, 1913) and ‘Ameslan’ (FantHI, 1972).

Archaeological evolution of ASL lexical items and influence of proximity to other sign languages (SupallaD, ClarkHI, et alD, H., 2015)

Documented in Bridges (BridgesD, 2023, 2007) that ASL semantics, lexical items, morphology, and phonology can roughly be broken into ASL components, fully and partially English markers, and onomatopoeia.

2

Signed English (SE)

Manual code 'umbrella'; not a language. English-based manual code(s) with a variety of additional grammatical and semantic markers. Though there are commercially-available "Signed English" curricula and dictionaries, 'Signed English' is more arguably an umbrella term — and not a singular system — for other related MCE systems (SEE1, SEE2, LOVE, 'Siglish' and 'Amelish,' et al.)

Analysis:

- In the preface to The Comprehensive Signed English Dictionary, BornsteinD and SaulnierD (1983) explain some of the methodology behind their MCE system. They describe SE’s (what actually appears to be SEE2) affixes and rationale behind their sign creation rules.

(Developed mid-1970s, Dr Harry BornsteinD, Gallaudet College; 1983, BornsteinD, Saulnier?, & Hamilton?)

3

Seeing Essential English (SEE1)

Now defunct; manual code, not a language. Formerly ‘SEE1’ and 'Morphemic Sign System' (cf., MilburnH, 1986); developed to "provide deaf/hard-of-hearing children with an intelligble visual-manual representation of English..." (Luetke-StahlmanH & MilburnH, 1996):

- compound words are broken in semantic morphemes/formed with separate signs (e.g., ‘butter’+ ‘fly’)

- like SEE2, follows a 'two out of three' rule; "if a word is spelled with the same letters and sounds the same (e.g., 'bear'/'bear'), it is signed the same way, even if the meaning of the two words differs" (Nielsen?, LuetkeH, & Stryker?, 2011). The same rule applies for homonyms (e.g., ‘bear’ and ‘bare’)

- heavy use of initialization (e.g., haVe, haD, haS)

- affixes, articles, and ‘to be’ (copula; 'Be,' 'Am,' 'Is,' 'aRe,' 'BeIng,' 'WaS,' 'WeRe,' 'BeeN') verb added

Analysis:

- WashburnH & AnthonyD (1974) explain the history and explanation of SEE1 production rules:

- Look at eighteenth-century LSF to see vestigial literal or initialized representations (initializations in bold):

- bon = good (Pl. XII; p 32)

- cent = hundred (Pl. XIII; p 34)

- mille = thousand

- autre = other

- chercher = seek/search; LSF curieux (Pl. XII; p 32) is etymn of ASL search

- David Anthony[D] was inspired by Ogden’s The Meaning of Meaning, where ‘a few hundred key words could do all the real work in their analyses of other words and idioms’ (19). Ogden determined that 850 words could be distilled into ‘Basic English.’

- Anthony determined that half of the lexical items in Basic English did not have signed cognates

- “One morning we came across GLASS as a new word, and the students were given the three different and common meanings of GLASS: 1) drinking glass, 2) window glass, and 3) eye glasses…. [Each] of these items had a different and unrelated sign. One boy said that this should not be so: a glass is a glass is a glass…. A few days later this same boy, came up to the teacher and said, “Better (sign).”

- G hand at eye, “for eye (glasses)”

- G hand sweeping down, “For window through see”

- G hand on other palm, “For water drink”

- The student in the class created several affixes and attempted to clarify words that had common roots but differing semantics.

- Look at eighteenth-century LSF to see vestigial literal or initialized representations (initializations in bold):

- Parodied in deaf literature and narratives; the "Mr. SeeTerp"D parody character demonstrates how ‘survivor’ humor is derived out of an over-the-top use of SEE as a communicative platform. Emblematic of its rhetorical conflict, SEE is often used in culturally Deaf discourse as a marker; those who use it are not ‘us,’ but ‘them.’

- Linguist and educator Byron Bridges also briefly lampoons the 2023 Super Bowl ASL interpretation by first referring to some canned SEE-type rendition of the anthem (beginning at 00:53)

4

Signing Exact English (SEE2)

Modified since original creation, evolving; manual code, not a language. (Formerly ‘SEE2’); similar to SEE1 and more similar to Signed English (BornsteinD, 1983) but:

- compound words are typically single signs and are more conceptually accurate (‘butterfly,’ not ‘butter’+ ‘fly’)

- signs tend to be semantically like ASL; one sounded word = one sign

- to create more single-sign semantic lexical items, sign 'families' are created through initialization (e.g., Car, Bus, Truck, Van, Station Wagon)

- dozens of invented initialized signs and affixes (prefixes [A-, In-, Re-] and suffixes [-Ness, -Tion, -Ing]) to create additional semantics

Analysis:

- GustasonD (1990) examines the origins of, reasons for, and common myths about SEE2 creation and usage.

- Comparison of a simultaneous ASL and SEE2 rendering; rhetoric aside, linguistically, what is happening in the SEE2 text?

- Interpreting colleague Daniel GreeneHI attempts to dispel misinformation and clarify the use of SEE2 for other interpreter practitioners. “My desire is for people to make educated choices about the language they use, which is why I want to make sure people who use the term SEE know what it actually is.” Includes video of SEE2 users.

(Developed 1972, Dr Gerilee GustasonD, Esther ZawolkowH, Donna PfetzingH)

5

Linguistics of Visual English (LOVE)

Now defunct; manual code, not a language. Visual recording system invented by Dennis WamplerD based on Seeing Essential English (SEE1). Used Stokoe Notation System (tab-dez-sig; StokoeH, 1960; StokoeH, CasterlineD, & CronebergD, 1965) to write sentences.

Analysis:

- NomelandD & NomelandD (2011) give a very brief description of Wampler’s LOVE system, highlighting its 1:1 coding and heavy use of initialization.

- GustasonD (1990) provides a brief description of the origin and use of Wampler’s LOVE system.

- Comprehensive article by LouH (1988) on the evolution of language usage in American deaf education and a very brief description of LOVE and how it was implemented in schools. (Other bonus information about other English-bound sign systems and approaches also given here.)

story(?) / quote / three / bear(s) / Goldilocks / way.in // woods / up / house / sitting.there / enter // that.there / father / bear / open.paper / read / newspaper / open.paper

"The story "Goldilocks and the Three Bears." Deep in the woods, there is a house sitting on a hill. (If you) go in, (you will see) there Papa Bear reading the paper."

(Developed 1972, Dennis WamplerD)

6

Rochester Method

Now largely defunct; manual code, not a language. Each lexical unit produced using individual phonemes of the American one-handed manual alphabet. Extensively used in schools for the deaf in the later 19th century to exactly represent written English phrases or sentences. Sometimes used in tactile/deaf-blind signing situations; some Deaf adults still use vestiges of this method.

Analysis:

- Parodied in deaf literature and narratives because of its difficulty for some users to reproduce and parse accurately.

- Sometimes used as language 'shibboleth' to determine a (typically hearing) signer's fluency.

(Developed 1878, Zenas WesterveltD, Superintendent, Western New York Institute for Deaf-Mutes, later Rochester School for the Deaf)

7

Written English

8

Spoken English

Other Manual Codes for English

9

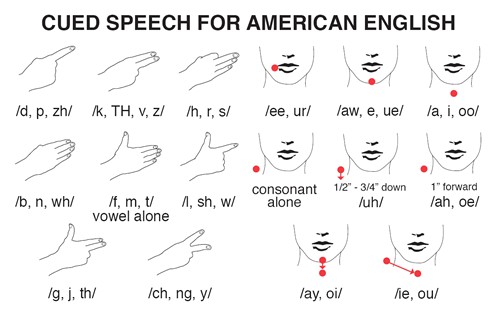

Cued Speech (CS)

Code; not a signed language. Uses eight non-semantic handshapes in eight different but related locations to visually represent spoken phonemes. Cued speech video sample and Cued Speech Association video samples. Learning to cue: Lesson 1 and Lesson 2 with a deaf CS user. Differences between cued speech and sign language.

10

Paget-Gorman Signed Speech (PGSS)

Code; not a signed language. British-based pantomimic, morphological based manual system. First experimental teaching of the system in 1964 with a group of deaf adults; PGSS first conceptualized in Britain in 1934 as a systematic pantomimic sign language whereby each word would have its own sign, with the signs presented in the same sequence as the words in the phrases or sentences to be signed. 37 basic 'signs,' 21 hand 'postures'; do not correspond to British Sign Language. Similar to Makaton, now used primarily with people who present with aphasia and/or speech disabilities.

11

Makaton

Code; not a signed language. Originally researched by Margaret Walker in the early 1970s and added vocabulary development in the mid-1980s to work with cognitively disabled deaf adults. Later and currently adapted to work with communicatively disabled hearing children and adults. Base vocabularies originally derived from British Sign Language (BSL) but adapted to work locally/regionally by deriving signs and gestures from other BANZSLs and other national SLs and their variants. Attitudes about the creation of Makaton and perceptions of BSL appropriation still persist.

(Research c. 1972–1973; vocabulary development 1985–1986, Margaret WalkerH, Botley Park Hospital, Chertsey, Surrey, UK

MCE Approaches

A

Translanguaging

Contact approach; not a language.

Current praxis and scholarship is moving away from CASE or PSE as a label. A more appropriate discussion and explanation of how/when signers utilize various codes and aspects of languages is translanguaging.

Translanguaging is a theoretical lens that offers a different view of bilingualism and multilingualism. The theory posits that rather than possessing two or more autonomous language systems, as has been traditionally thought, bilinguals, multilinguals, and indeed, all users of language, select and deploy particular features from a unitary linguistic repertoire to make meaning and to negotiate particular communicative contexts. (Vogel & García, 2017)

Analysis:

- Current debate about CASE or PSE has been elevating in recent years. This recent discussion suggests that deaf families do not purposely 'use PSE' in their language choices, but instead translanguaging and translanguage.

- cf. Han, L., Wen, Z., & Runcieman, A. J. (2023) Interpreting as Translanguaging: Theory, Research, and Practice

- Han, L., Wen, Z., & Runcieman, A. (2023). Interpreting as translanguaging: Theory, research, and practice. Elements in translation and interpreting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009375870

- Hirsch, T. & Kayam, O. (2020). “We Speak Pidgin!” Family language policy as the telling case for translanguaging spaces and monolingual ideologies. Open Linguistics 6(1), 642-650. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2020-0037

- Otheguy, R., García, O. & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3), 281-307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

- Vogel, S., & García, O. (2017, December 19). Translanguaging. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Retrieved 22 Jan. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/education/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-181

- Wei, L. (February 2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039 and https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323720294_Translanguaging_as_a_Practical_Theory_of_Language

- Lee, B. & Secora, K. (2022). Fingerspelling and its role in translanguaging. Languages7(4), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040278

B

Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE)

Contact approach; not a language. CASE (Conceptually Accurate Signed English) is a popular alternative to Signed English, sometimes called PSE (Pidgin Signed English[add Woodward 1973 SLS 3, pp 39-46 here]); combines ASL signs and concepts in an MCE form.

Analysis:

- Current debate about CASE or PSE has been elevating in recent years. This recent discussion suggests that deaf families do not purposely 'use PSE' in their language choices, but instead translanguaging and translanguage.

- cf. Han, L., Wen, Z., & Runcieman, A. J. (2023) Interpreting as Translanguaging: Theory, Research, and Practice

C

Sign Supported Speech (SSS)

Contact approach; not a language. SSS (Sign Supported Speech) consists of voicing spoken English and signing an MCE. Sometimes called Simultaneous Communication (SimCom) or Total Communication (TC).

Analysis:

References

- ↩ StringhamHI, D. (2019). Comparative American Sign Language/English Continuum. https://www.academia.edu/40262938/Comparative_American_Sign_Language_English_Continuum_2019_.

- ↩ http://intrpr.info/library/stringham-asl-english-continuum.pdf. Also printed in HumphreyHI, J., ClarkHI, L., FeatherstoneDI, J., and Ross IIIHI, W. F. (2020). You want to be an interpreter (5th edition). Vancouver, WA: H&H Publishing.

- ↩ Wikibooks, Visual Language Interpreting/Tools of the Trade, initial creation 3 May 2014; last content edit 11 Mar 2016.

- ↩ RileyH, B. (2011). The American sign language–English language–contact situation. Lengua de Señas e Interpretación, Montevideo, 2, 93–117.

- ↩ CrystalH, D. & CraigH, E. (1978). Contrived sign language. In I. M. SchlesingerH & L. NamirH, Sign language of the deaf: Psychological, linguistic, and sociological perspectives, 141–166. New York: Academic Press. (Discussion of 'contrived signing systems' on pp 161–166.)

- ↩ "Contact sign." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contact_sign

- ↩ CokleyH, D. (1983). When is a pidgin not a pidgin? An alternate analysis of the ASL-English contact situation. Sign Language Studies, 38 (Spring 1983), 1–24. (doi: 10.1353/sls.1983.0017).

- ↩ LucasH, C. & ValliDI, C. (1992). Language contact in the American Deaf community. In C. ValliDI & C. LucasH (eds), Linguistics of American Sign Language: An introduction, 458–480. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. (cf., LucasH & ValliDI, 1988, 1989, 1991.)

- ↩ WoodwardH, J. (1973). Some Characteristics of Pidgin Sign English. Sign Language Studies, 2(3), 39–46. (doi:10.1353/sls.1973.0006).

- ↩ "Manually coded English." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manually_coded_English

- ↩ DavisD, J. E. & McKay-CodyD, M. (2011). Signed languages of American Indian communities: Considerations for interpreting work and research. In R. L. McKeeH & J. E. DavisD (eds.), Interpreting in Multilingual, Multicultural Contexts, 119–157. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. (cf., DavisD, 2007; Wurtzburg? & Campbell?, 1995; McKay-CodyD, 1997, 1998, 1999.)

- ↩ RobinsonD, O. (2019). "The 1817 Origins Myth," published 30 Nov 2019; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8M40MarjY0c.

- ↩ MalleryH, G. (1880). Introduction to the study of sign language among the North American Indians: as illustrating the gesture speech of mankind. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- ↩ "ASL: Colorless?" (Laurene SimmsD) 17 Mar 2019; https://youtu.be/StHsChYWGC4?t=63 (discussion of multiple ethnic etymologies in 'The birth of ASL,' 1:33–4:45).

- ↩ Loew?, R. C., AkamatsuH, C. T., & LanavilleH, M. (2000). Two-handed manual alphabet in the United States. In K. EmmoreyH & H. LaneH (eds.), The signs of language revisited: An anthology to honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima, 215–227. New York: Psychology Press. (https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410604972).

- ↩ (References to Kentish, Henniker, Martha's Vineyard, and Sandy River Sign Languages.) LaneH, H., PillardH, R. C., & HedbergD, M. (2011). The people of the eye: Deaf ethnicity and ancestry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Other North American and parenthetical similar international communities include references to numerous other shared community sign systems [Kusters, 2009], Katwijk aan Zee Sign Language [Netherlands; Nyst, 2015] and Lantz Mill Sign Language (Shenandoah County, Virginia [Brockaway, 2022])

- ↩ (most regional contact sign systems are unrecorded; still gathering)

- ↩ (unknown; possible to gather?)

- ↩ Clark, William PhiloH (1885). The Indian sign language, with brief explanatory notes of the gestures taught deaf-mutes in our institutions for their instruction and a description of some of the peculiar laws, customs, myths, superstitions, ways of living, code of peace and war signals of our aborigines. Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co.

- ↩ DavisD, J. E. (Online publication: May 2017). Native American signed languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.42.

- ↩ HillD, J., McCaskillD, C., BayleyH, R., & LucasH, C. (2015). The Black ASL (American Sign Language) Project: An Overview. In J. BloomquistH, L. J. GreenH, & S. L. LanehartH (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of African American Language, 316–337. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199795390.013.38).

- ↩ McCaskillD, C., LucasH, C., BayleyH, R., & HillD, J. (2020). The hidden treasure of Black ASL: Its history and structure. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. (See also related presentations and references at http://blackaslproject.gallaudet.edu and The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL video presentations/data collection.)

- ↩ (cf., LaneH, PillardH, & HedbergD, 2011. References to British SL mixed with Martha's Vineyard SL.)

- ↩ KitzelH, M. E. (2013). Chasing ancestors: Searching for the roots of American Sign Language in the Kentish Weald, 1620–1851. Unpublilshed thesis. University of Sussex.

- ↩ LaneH, H., PillardH, R., & FrenchH, M. (2000). Origins of the American Deaf-World: Assimilating and differentiating societies and their relation to genetic patterning. Sign Language Studies, 1(1), 17-44.

- ↩ GroceH, N. E. (1985). Everyone here spoke sign language: Hereditary deafness on Martha's Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↩ Quinto-PozosHI, D. G. (2002). Contact between Mexican Sign Language and American Sign Language in two Texas border areas. Unpublished dissertation. University of Texas at Austin.

- ↩ Quinto-PozosHI, D. G. (2008). Sign language contact and interference: ASL and LSM. Language in Society, 37, 161–189. (doi: 10.10170S0047404508080251).

- ↩ PelissierD, P. (1856). Iconographie des signs faisant partie de l'enseignement primaire des sourds-muets. Paris: Chez L'Auteur.

- ↩ LaneH, H. (1989). When the mind hears: A history of the deaf. New York: Vintage.

- ↩ CagleD, K. M. (2010). Exploring the ancestral roots of American sign language: Lexical borrowing from Cistercian sign language and French sign language. The University of New Mexico. Unpublished dissertation.

- ↩ BrownH, J. S. (1856). A vocabulary of mute signs. Baton Rouge, LA: Daily Gazette and Morning Comet.

- ↩ BrownH, J. S. (1860). A dictionary of signs and of the language of action, for the use of Deaf-Mutes, their instructors and friends; and, also, designed to facilitate to members of the bar, clergymen, political speakers, lecturers, and to the pupils of schools, academies, and colleges, the acquisition of a natural, graceful, distinctive and life-like gesticulation. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana Institution for the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind.

- ↩ StringhamHI, D. (2019). "A Language of Action": James Smedley Brown and the First American Dictionary of Sign Language. In B. EldredgeH, D. StringhamHI, and B. JarashowD. Waypoints: Proceedings of the Sixth Deaf Studies Today! Conference. Utah Valley University: Orem, Utah.

- ↩ Baker-ShenkH, C. & CokelyHI, D. (1980). American Sign Language: A teacher's resource text on grammar and culture. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- ↩ VeditzD, G. (1913). Preservation of the sign language. Film. The National Association of the Deaf. (All 'Preservation Series' films by the National Association of the Deaf can be found [with annotations] at the Historical Sign Language Database at Georgetown University, curated by Ted Supalla and other contributors.)

- ↩ FantHI, L., Jr. (1972). Ameslan: An introduction to American Sign Language. Silver Spring, MD: National Association of the Deaf.

- ↩ "Georgetown Professor Ted Supalla's ASL Archaeology Presentation at RIT," published 4 Sep 2015; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLW7ASfH77I. cf. SupallaD, T. & ClarkHI, P. (2015). Sign Language Archeology: Understanding the Historical Roots of American Sign Language. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press and materials at the Historical Sign Language Database.

- ↩ "What's ASL?" published 12 Jan 2023; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7wsDhzGvOc.

- ↩ BridgesD, B. W. (2007). Making Sense of Visual Mouth Movement: A Linguistic Description. Lamar University. Unpublished dissertation.

- ↩ 'Siglish' is also mentioned at "Siglish: an old term of Signed English" and Murphy?, H. J. & FleischerD, L. R. (1977). The effects of Ameslan versus Siglish upon test scores. Journal of American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association (JADARA), 11(2; October 1977), 15–18.

- ↩ There is little to no extant reference of 'Amelish'; the only seeming reference to it is "This term was coined by Bernard BraggD from Texas. This method uses lots of ASL & fs [fingerspelling] in English order." (https://deaf-info.zak.co.il/d/deaf-info/old/methods.html.)

- ↩ BornsteinD, H., Saulnier?, K, & Hamilton?, L. (1983). The comprehensive signed English dictionary. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- ↩ BornsteinD, H. (1974). Signed English: A Manual Approach to English Language Development. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 39(3), 330–342. (doi:10.1044/jshd.3903.330).

- ↩ Nielsen?, D. C., LuetkeH, B., & Stryker?, D. S. (2011). The importance of morphemic awareness to reading achievement and the potential of signing morphemes to supporting reading development. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 16(3), Summer, 275–288. (doi:10.1093/deafed/enq063).

- ↩ MilburnH, W. (1986). 1986 morphemic list. Amarillo, TX: Amarillo Independent School District Regional Educational Program for the Deaf.

- ↩ WashburnH, A. O., & AnthonyD, D. A. (1974). Seeing Essential English: A sign system of English. Journal of Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology, 7(1), 18-25.

- ↩ "Star Spangled Banner Parody: Mr. SeeTerp" (John MaucereD), published 3 Feb 2014; https://vimeo.com/groups/73395/videos/85760406.

- ↩ "ASL national song during Super Bowl" (Byron Bridges D), published 13 Feb 2023; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfWbfjtU4sE (starts 00:53).

- ↩ Luetke-StahlmanH, B. & MilburnH, W. O. (1996). A History of Seeing Essential English (SEE I). American Annals of the Deaf, 141(1), 29–33.

- ↩ "A New Signing Exact English Dictionary," (James Kilpatrick, Jr.H), published 1 Dec 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upBJHVFkv50. Compare also "SEE Signing Exact English Training," https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iOu_5v3zixM.

- ↩ GustasonD, G. (1990). Signing exact english. In H. BornsteinD (ed.), Manual communication: Implications for education, 108–127. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- ↩ "ASL vs. SEE Comparison | ASL - American Sign Language," (ASLTHAT! [Joseph WheelerD]), published 19 Oct 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvqZ83pS0B4

- ↩ GreeneH, D. (2012, 5 Sep). "SEE: Allow me to disabuse you of a common misnomer." http://danielgreene.com/2012/09/05/see-allow-me-to-disabuse-you-of-a-common-misnomer

- ↩

- GustasonD, G. (1990). Signing exact english. In H. BornsteinD (ed.), Manual communication: Implications for education, 108–127. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- ↩ "Stokoe Notation," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stokoe_notation. (cf., History of American Sign Language: Stokoe Notation and StokoeH, W. C. (2005; original 1960). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American Deaf. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 10(1), 3–37. (doi:10.1093/deafed/eni001). (Originally published as Studies in Linguistics, Occasional Papers 8 (1960), by the Department of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo, Buffalo 14, New York.)

- ↩ "Signs of Change: William Stokoe's Research into American Sign Language," published 3 Mar 2017; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-N2dSl6ZBU. (Student project: StoughtonH, J., Individual Documentary, Senior Division, National History Day 2017)

- ↩ StokoeH, W. C., CasterlineD, D. C., & CronebergD, C. G. (1965). A dictionary of American sign language on linguistic principles. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet College Press.

- ↩ NomelandD, M. M. & NomelandD, R. E. (2011). The Deaf community in America: History in the making. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

- ↩ GustasonD, G. (1990). Signing exact english. In H. BornsteinD (ed.), Manual communication: Implications for education, 108–127. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

- ↩ LouH, M. W. (1988). The history of language use in the education of the Deaf in the United States. In M. StrongH (ed.) Language Learning and Deafness. London: Cambridge University Press.

- ↩ "Rochester Method - American Deaf Culture," (Terrell Brittain, University of Houston) published 10 Nov 2020; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gb1EH1pijHA.

- ↩ "Billy KelmanD," published 27 Aug 2008; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fYAVL1Dxokk.

- ↩

- ↩ "Cued Speech," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cued_speech.

- ↩ "Sir Richard PagetH," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Richard_Paget,_2nd_Baronet.

- ↩ "Makaton," https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Makaton.

Definitions and Foundation

American Sign Language

Signed English

Seeing Essential English (SEE1)

Signing Exact English (SEE2)

Linguistics of Visual English (LOVE)

Rochester Method

Cued Speech

Paget-Gorman Signed Speech (PGSS)

Makaton

Page last modified:

All relationships relative; overlapping approaches drawn for distinction and not for accuracy.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 United States License. This license grants you permission to share (copy, distribute, and transmit the website) and remix (to adapt this work) under certain conditions and understandings. This license does not apply, however, to work claimed by other authors and producers. Additionally, every intent has been made to make materials available via “Fair Use,” (§107 to 118, Title 17, US Code); the content and downloadable materials on this page are solely for the benefit of the students enrolled in these courses.

Page © Doug Stringham, Utah Valley University; revised 2021, 2019, 2018, 2012, 2011, 2008, 2006. APA citation: Stringham, D. (). Comparative ASL/English language continuum.

- Changelog

- 24 Jan 2023: v.16; added definitions of 'manually coded languages' and updated links.

- 6 Sep 2022: v.15; removed "

document.write(document.lastModified)" from 'last modified' script because this is deprecated/considered a poor practice (https://stackoverflow.com/questions/802854/why-is-document-write-considered-a-bad-practice - Jan–May 2022: v.14; Added/clarified additional references, corrected links. Added

<-webkit-background-clip: text>; and<-webkit-text-fill-color: transparent>to continuum gradient. - 29 Dec 2021: v.13; redesigned page to add visual weight to Purposes & Definitions; redesigned v1 and v2 (apply gradient to a div outside of

<main>) so this will work better on mobile devices (needs better spacing and realignment); updated Purposes, (8) Written English, and (9) Spoken English; error in footnote display; current error in approach cloud display. Safari does not display continuum correctly but should with the continuum redesign. - 10 Dec 2021: v.12; returned to Inter as master typeface, including contextual alternate characters. Began looking at Tailwind CSS as a replacement CSS/layout tool.

- 20 Nov 2021: v.11; completely rebuilt page, fixed Bootstrap organization errors. Rebuilt continuum to fit the layout correctly; need to build to fit narrow viewports, reorganized h1–h4. Fixed font stack. Cleaned up introduction and consolidated text. Need to fix auto-footnote creation; numbering is off by one. Added alt text.

- 13 Aug 2021: v.10; added dividers in the references section to make it easier to identify references relevant to language/code sections. Added Supalla reference and updated link styles, formats.

- 06 July 2021: v.09; added more references to ASL influences, corrected links and references for accuracy. Updated CSS for better fidelity across all main body styles. Updated footer to be consistent with other projects.

- 18 Feb 2021: v.08; removed Inter typeface, back to using system font stack (https://css-tricks.com/snippets/css/system-font-stack); edited 'Purposes' and 'Definitions' paragraph.

- 03 Feb 2021: v.07; Nuance breakpoints, specifically for when references change from columns to single-width. Nuance line-height for references. Add a page modified indicator. Added indigenous signs/etymology reference. Experimenting with Inter typeface. Added

<-webkit-font-smoothing: antialiased; -moz-osx-font-smoothing: grayscale>to text styles. - 01 Feb 2021: v.06; Added references for signed English (Siglish, Amelish) and corrected page numbers for The Black ASL Project, corrected links. Hide the continuum when the width gets too narrow. Fix circle numbers. Fix author citations.

- 31 Jan 2021: v.05; Added more references, corrected links.

- 25 Jan 2021: v.04; Added several more references, corrected links. Added explanation for gestural English-derived MCEs. Added new citations. Change layout from four to three columns at full width.

- 13 Jan 2021: v.03; Added more references, need to be streamlined and linked

- 28 Dec 2020: v.02; add js solution for automatic reference numbers; don't require manual curation. Renumber themselves based on adding to the ordered list.

- 26 Dec 2020: v.01; pull from Bootstrap 5 for base, custom typographic stylesheet

- Roadmap:

- Fix footnote script issues

- Get off Bootstrap and create simple flexbox/grid system

- Fix mobile version; remove styling and enhance vertical design

- Fix print version; remove unneccesary styling and fit to printed page

- Make stylesheet consistent with rid-cpc.html, etc. and new v.8 of intrpr.info

Fix .circle-number class- Add more references

- Figure out the best way to set footnote text with punctuation (before or after?)